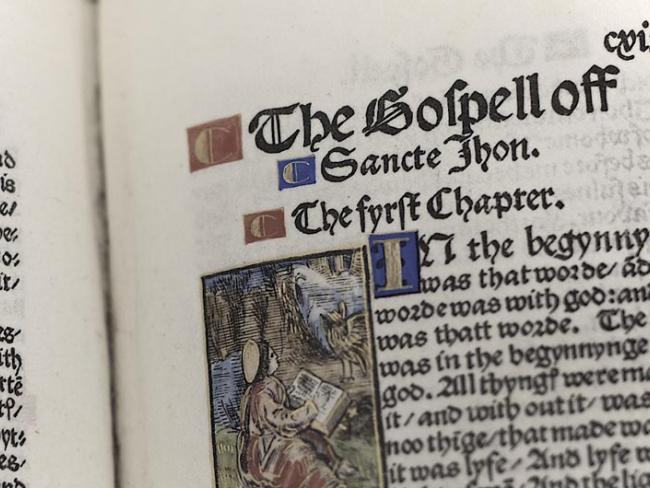

The Gospel of St John in Tyndale’s 1526 Bible, now in the British Library.

Around 500 years ago William Tyndale produced a Bible in English – and paid for it with his life…

William Tyndale (1494-1536) was one of the great independent minds who set England on a course to think and act for ourselves – helping to make English a great language of poets and writers the world over.

The earliest of these thinkers were often Church men – since the Church educated those who were going to work for them. Two hundred years earlier John Wycliffe had asserted that people could congregate and think for themselves without the need for clergy.

Influence

Wycliffe and his followers the Lollards were denounced and persecuted as heretics by the Church. But their influence continued into Tyndale’s time when capitalism and a working class were beginning to develop within the feudal order. The Catholic Church, headed by the pope in Rome, still controlled thought and ideas. His local agents were the clergy, whose use of Latin excluded almost everyone else.

Like Wycliffe, William Tyndale also studied theology and became a popular preacher. Growing up in the Gloucestershire countryside, he knew the people working on the land, who were mostly illiterate. Around 90 per cent of men and 98 per cent of women were then illiterate, according to academic studies based on parish register entries.

‘A good translation of the Bible was part of the struggle for independence of thought…’

Tyndale saw the need for a good English translation of the Bible as a key part of the struggle to widen access to an independence of thought. Speaking of the Pope, he said, “I wyl cause a boy that driveth the plough to know more of the Scripture, than he doust.” A great linguist, he executed an ambitious plan to translate the Bible into the English spoken by working people.

By Tyndale’s use of his talent, the illiterate ploughboy could then hear and understand the Bible read out in his own language, consider and discuss it, make up his own mind about the meaning. It was a great stimulus to the growth of literacy and surely to the long-term development of democracy too!

For centuries, probably millennia, ploughmen had walked and talked together along the long ridges and furrows typical of fields in medieval England. Now better informed, their discussions could become much more confident. They could also take note of what was not mentioned in the Bible – such as the Papacy, sacraments, confession, payment for indulgences and so on.

After the Church authorities heard his views, Tyndale had to flee England. He hid out in Germany and the Netherlands to continue translating. Newly established printers there published his work and smuggled copies into England. While spies and agents of the Pope, King Henry VIII and the Holy Roman Empire searched for him, local protestants and printers helped him.

Meaning

Tyndale knew that the Latin Bible was not his starting point, so his translation is very different from the earlier one of John Wycliffe. He knew that to find the meaning he had to get back to the languages in which it was originally written, Greek and Hebrew. That enraged the Church.

In England Tyndale’s New Testament translation was eagerly bought and circulated, though mere possession of it was grounds for torture and burning. The Establishment of the day were obsessed with eradicating Tyndale and his translation.

The Bishop of London bought up an entire edition of 6,000 copies and burned them on the steps of the old St Paul’s Cathedral. Sir (later Saint) Thomas More called William Tyndale “a hell hound in the kennel of the Devil.” He pursued and tortured Tyndale’s old friends.

In 1536 Tyndale was finally captured by the agents of the Holy Roman Empire, taken to Belgium and burnt at the stake, but not before he had translated the New Testament and a good part of the Old. These later became the basis of the King James, “Authorised”, Version of the Bible.

Tyndale’s creative mind worked magic on the texts. Melvyn Bragg, in his book William Tyndale: a short biography, pointed out that he found and used the monosyllables that have made great English prose and poetry ever since. Almost as an accidental by-product, he gave us a huge array of great phrases – some of which come out of his childhood in the Cotswold countryside, some of which were taken from Anglo-Saxon and Hebrew, all of which he transformed into our everyday language.

Shakespeare was familiar with Tyndale’s language and played with it. See what he does with Tyndale’s translation of 1 Corinthians 2.9: “Eye hath not seen, nor ear heard, neither have entered into the heart of man, the things which God hath prepared for them that love him”. Shakespeare and his audience knew it so well that he could conjure up this from Bottom in A Midsummer Night’s Dream: “The eye of man hath not heard, the ear of man hath not seen,...nor his heart to report what my dream was!”

The phrases Tyndale gave to our language include: “let there be light”, “my brother's keeper”, “knock and it shall be opened unto you”, “a moment in time”, “fashion not yourselves to the world”, “seek and ye shall find”, “ask and it shall be given you”, “judge not that ye be not judged”, “the salt of the earth”, “a law unto themselves”, “filthy lucre” and many more.

Until recently, Tyndale’s creation of the core text that formed the King James Bible was erased from the record, though he gave his life for it. Born of a deep love of his country, its people and language, his legacy is knowledge and poetry.