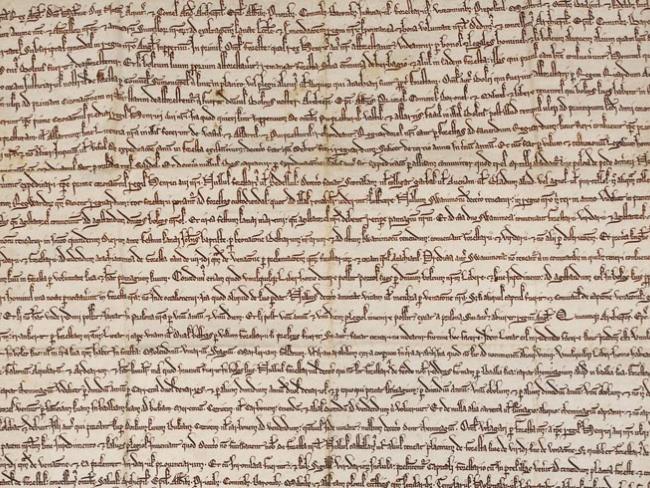

British Library copy of the charter – one of three – made with additions in 1225. Photo public domain.

A little-known event in medieval times is still of interest today – it tells us how people can exercise their power…

In 1217 the Charter of the Forest re-established for “free men” rights of access to the royal forests that had been eroded by King William the Conqueror (1066-1087) and his heirs.

The charter was part of a peace settlement after a period of civil war. In many ways it complements the better known Magna Carta. Many of the charter’s provisions remained in force for centuries afterwards.

To the Normans, who invaded England 150 years earlier, “forest” meant an enclosed area where the monarch, or sometimes another aristocrat, had exclusive rights to animals of the chase and the greenery (“vert”) on which they fed.

Forests included large areas of commons such as heathland, grassland and wetlands. These areas could be used for food production and for grazing as well as for fuel and other resources.

Before the Norman takeover, two aspects of life in Anglo-Saxon England were different. First, Anglo-Saxon kings – though great huntsmen – never set aside areas declared to be “outside the law of the land”.

And secondly, commoners – typically peasants or villagers – did have some rights to use forests and common land. The contrast with Norman forest law was marked; Anglo-Saxon ways were less rigid and less exclusive.

The charter redressed some applications of the Anglo-Norman forest law, under which the Norman kings had begun to reserve some of England’s vast forests for their own private use. People resented the cruel punishments that forest courts gave out to those who broke the rules.

‘Many of the charter’s provisions remained in force for centuries afterwards…’

These royal enclosures deprived the common man of the ability to forage for food, hunt for meat or gather firewood. These grievances were among the issues raised at the time of Magna Carta in 1215. Significantly they were of lesser concern to the barons opposing the King and so failed to be incorporated in the great charter itself. Two years later, however, this matter received its own charter, which was reissued alongside Magna Carta in 1225.

At its widest extent, royal forest covered about a third of southern England and became an increasing hardship on commoners trying to farm, forage and otherwise use the land they lived on: for example, in charcoal burning industries; pannage (pasture for pigs), estover (collecting firewood), agistment (grazing), or turbary (cutting of turf for fuel).

Pasture

The first clause of the charter protected common pasture in the forest for all those “accustomed to it” And clause 9 added, “Henceforth every freeman, in his wood or on his land that he has in the forest, may with impunity make a mill, fish-preserve, pond, marl-pit, ditch, or arable in cultivated land outside coverts, provided that no injury is thereby given to any neighbour.”

Clause 10 repealed the death penalty (and mutilation as a lesser punishment) for capturing deer (venison), though transgressors were still subject to fines or imprisonment. Clause 13 declared, “Every freeman shall have, within his own woods, ayries of hawks, sparrow-hawks, falcons, eagles and herons: and shall have also the honey that is found within his woods.”

Special verderers’ courts were set up within the forests to enforce the laws of the charter and officials were employed to enforce fines and punishments. At times their annoying behaviour led to rural riots, as in Cheshire in the 1350s.

Historians disagree about the significance of the charter. Some believe it asserted not only the rights of ordinary people to access the commons for the means of livelihood and shelter, but also that it represented a constitutional victory for ordinary people over the wealthy elite, opening or reopening forests to the use of non-aristocrats.

Others quibble that the concessions in the charter were only granted to “free men”. It excluded the unfree, a large proportion of the population, and allowed lords to make the forest profitable; peasants using forests had to pay to let their pigs root or to gather loose wood or cut trees.

Rights of the free

Undeniably, the charter was a vehicle for asserting the right of commoners against the privileged landed class that normally could employ the power of the state for their own interests. But objectively it was not about the rights of the poor but the rights of the free.

The charter did not apply to serfs (agricultural labourers tied by the feudal system to working on the lord’s estate) or villeins (feudal tenants entirely subject to a lord or manor). Probably less than half of the population benefited. But for free men it was a vital change that reversed rights eroded for 150 years.

The charter was undoubtedly, for its time, a radical assertion of practical freedoms. As with most laws, its provisions did not emerge out of the blue, nor was it a piece of altruistic benevolence handed down from those on high.

The free commoners had for centuries been exercising, or attempting to exercise, many of the activities allowed in the act. The ultimate force behind the passing of the legislation was the refusal of the free to be denied what they had before.

Equally, after the charter was agreed, the free commoners continued a struggle to defend, uphold and ensure proper implementation of the act. That was the necessary impetus sustaining their rights and which kept their acknowledged place within the forests and commons alive.

Then as now, it is the people who make things happen and then sustain them.

• A longer version of the article is on the web at www.cpbml.org.uk