27 October 2022

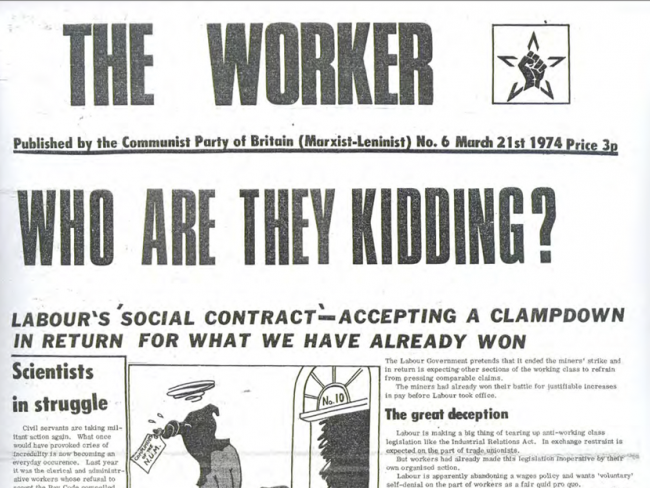

Headline from The Worker in 1974 warning of the dangers of the new Social Contract.

Heightened class struggle in the early 1970s was neutered by a Labour Government and trade union establishment working in tandem…

Many confident working class struggles erupted in the early 1970s across a huge range of disputes and sectors. The highlights were the engineering union’s destruction of the 1971 Industrial Relations Act and the miners’ victory over pay in the face of the imposition of a three-day week.

After this tricky period for the establishment, the incoming 1974 Labour government stabilised capitalism, coordinating moves to dampen down industrial action. It preached class conciliation by dangling bribes to the unions in exchange for moderation of wages.

The Labour government promised to repeal the Industrial Relations Act, introduce food subsidies and freeze council rent increases. In return, the Trade Union Congress (TUC) said it would ensure union cooperation in submitting to voluntary wage restraint “to combat rising inflation” – the Social Contract.

Opposition

The Social Contract came about after the Conservative government of 1970-74 led by Edward Heath failed to control the enormous surge of industrial struggle. This was fuelled by opposition to anti-union legislation and rampant inflation.

Heath introduced a wage and price freeze in November 1972, followed by a mandatory prices and incomes policy. Many trade unions objected to this and struggled against it. The 1973 world energy crisis strengthened the position of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM); it began industrial action on 12 November that year in pursuit of higher pay.

The government immediately announced a national emergency. They met the NUM leadership 16 days later, offering pay and other concessions, which were refused. In December Heath announced the imposition of a three-day working week to conserve energy.

Intervention

A few weeks later, in January 1974, the TUC general secretary Len Murray intervened. He promised that if the government enabled an agreement between the NUM and the National Coal Board, their employer, then no other union would make a similar claim.

The TUC’s attempt to override the NUM’s autonomy failed. In any case, the Cabinet decided not to accept their offer; on 4 February, the NUM membership began a national strike. Heath called a general election on the issue of “Who governs Britain?”. The Conservative government lost its majority.

The Labour Party under Harold Wilson formed a minority government on 4 March 1974 and later gained a small majority after the subsequent October 1974 election. Heath’s ministry had failed, but the capitalist establishment was still desperate to control the enormous surge of industrial struggle.

State control

Towards the end of the Heath government and reacting mainly to the Industrial Relations Act, the unions and Labour’s National Executive Committee formed a liaison committee. This tentatively sketched the notion of a Social Contract which would expand the frontiers of state control and incorporate trade unions in the process.

The liaison committee agreement was formalised and implemented once the new Labour government took office. Its aim was for organised labour to cooperate with the state and to drop the turbulent industrial relations of the previous period. The TUC willingly agreed.

Arrogance

In return for the repeal of the Industrial Relations Act, the Labour Government arrogantly declared it was “entitled to understanding and support in its efforts to produce a solution to grave economic and social problems”. None of those problems were of workers’ making; the government went on to solve only a few of them.

In March 1974, our Party warned that Labour’s Social Contract meant the working class accepting a clampdown in return for what they had already won by themselves. The Labour government pretended it ended the miners’ strike; it did not – the miners had effectively won their battle for wage increases before Labour took office. But Labour expected other workers to refrain from pressing comparable claims.

Deception

Labour claimed it had abandoned a wages control policy; that was a deception. Industrial action by other groups of workers had made the Counter-Inflation Act of the Heath government unworkable.

Labour also made a big play about tearing up anti-working class legislation like the Industrial Relations Act. Another distortion: workers led by the engineering union had already made this legislation inoperative by their own organised resistance and strike actions.

‘Workers were sold the big lie that what already had been won by their own struggle was a gift from Labour…’

Workers were sold the big lie that what already had been won by their own struggle was really a gift of the Labour government. It also peddled the fairy tale that if workers were moderate in their demands, they would be better protected than by taking industrial action for higher wages.

The reality was different – workers accepted greater exploitation, and the government abandoned “voluntary” wage restraint. But the Labour government and the TUC were taking on more than pay claims.

Corporate state

In June 1974 the CPBML spelled out the risks in this way: “The Labour Party is the major vehicle for the advancement of the corporate state; a fascist state rule which seeks to destroy the weapons of workers’ struggle and to subjugate the working class. The Labour Party’s pernicious role is to attempt to secure the acquiescence of the working class to its own enslavement…

“The right of collective bargaining, like the emancipation of the working class, is not something which can be bestowed on us from high. It can only be won and maintained by our own continuous struggle.”

Different times

The 1970s were different from today. Large parts of the British economy were monopoly state capitalist in character – owned by the government and covering a whole industry like gas or electricity generation. But being state controlled did not automatically mean they were good for workers.

‘Unions adopted a legalistic approach instead of mass struggle…’

Introduction of the 1974 Trade Union and Labour Relations Act and the 1975 Employment Protection Act by the Labour government marked a shift in the way unions operated. Instead of bringing the mass of members into the struggle to win a dispute, they tended more and more to adopt a legalistic, compensation-based approach.

This distanced members from the day-to-day issues of unfair dismissal, job losses or workplace reorganisation, as well as pay. It lessened membership activity and changed union ethos. Union density rose during the 1970s – at one point half of those employed were in a union – reaching peaks never achieved before or since.

By July 1975, the Labour government was no longer prepared to tolerate purely voluntary wage restraint. It introduced a formal incomes policy within the Contract to operate in stages over the following four years, tapering wage increases downwards.

At first the Labour government managed to prevent pay rises generally exceeding the “agreed” level – ie the cap it dictated. But the capitalist economy continued to deteriorate in Britain, and the government’s sweetheart promises did not fully materialise.

One-sided

High rates of inflation, rising unemployment, an IMF loan, deflationary spending cuts and interest rate increases exposed the one-sided nature of trade union commitments to the Contract. In 1974 inflation hit 16 per cent, rising to a record high of 24 per cent the following year; in 1978 it was still over 8 per cent. Between 1975 and 1980 real wages fell by 13 per cent – punitive cuts for workers and higher profits for employers.

The early social contract discussion included vague sentiments about returning to full employment. But nothing came of it: the average annual unemployment rate rose from 5.4 per cent under the Heath government up to 7.9 per cent in the period from 1974 to 1979.

Wilson’s government lost a parliamentary vote on public expenditure in March 1976, which triggered a sterling crisis. On 5 March 1976 sterling suffered its largest fall in a single day and continued to drift.

Loan

James Callaghan replaced Wilson as prime minister at the beginning of April. He had to secure a loan of nearly $4 billion from the International Monetary Fund, equivalent to around $19 billion today; it was at the time the largest loan the IMF had made.

This crisis was attributed to several factors, the 1972 Conservative “Dash for Growth” Budget, the 1973 oil crisis, and a deficit in both the balance of payments and public spending. None of these factors were of workers’ making. But as usual, the Confederation of British Industry called for them to show a spirit of sacrifice

As a result of the IMF loan and devaluation of sterling, Callaghan instigated deflationary spending cuts in public spending and increased interest rates. This further worsened economic problems for workers.

Strikes

Observance of the Social Contract began to fray and trade union members called for wage increases in line with and above inflation. In 1977 the number and extent of strikes had risen markedly compared to the previous year. By September the annual TUC conference voted decisively for a return to collective bargaining within the next year.

‘Unions continued to support the government…’

Yet unions mostly continued to support the government, at least to the extent of not rocking the boat or openly challenging it, and discouraged any others from doing so. The most notable example was the TUC’s refusal to support the Fire Brigade Union strike in November 1977 for a pay rise greater than allowed under the Contract. The government deployed the army, won the dispute and the Contract remained just about intact.

By 1978 the limits on pay increases under the Social Contract were unacceptable. Callaghan and Denis Healey, Chancellor of the Exchequer, decided to impose a limit of 5 per cent on pay increases in the face of a deteriorating quality of living for most workers. Even then the TUC continued to avoid confrontation with the government.

Broken

Then on 22 September 1978 a strike started at Ford Motor Company. It lasted eight weeks and ended with Ford offering a 17 per cent pay rise to their workers. The Labour government failed to pass a bill through parliament to apply sanctions against Ford for breaking the pay limit; the Social Contract was effectively broken.

Class conciliation, especially when it seeks to constrain future actions, inevitably veers towards class collaboration so long as ruling class interests remain in control.

The practice of the Social Contract led to the voluntary emasculation of trade unions and a greater passivity on the part of the working class. The ruling class will always attempt to bind workers to promises of restraint, but will always excuse themselves from commitments when they deem it necessary. But it’s folly for workers to voluntarily surrender control to the opposing class.

Hopefully we learn from the mistakes of the past. We should beware any calls for a new Labour government being encouraged into office to forge a new social contract in return for the repeal of anti-trade union legislation, the provision of energy subsidies, and a freeze on rent and mortgage increases and so on.

A shorter version of this analysis will appear in the November/December edition of Workers magazine