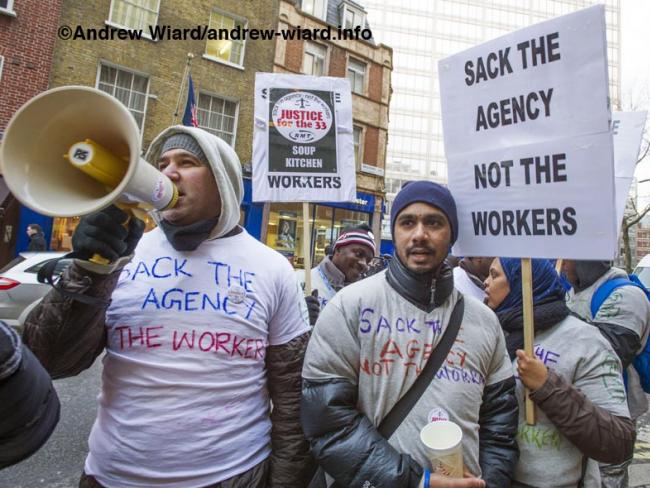

London, January 2013. RMT protest outside London Underground head office demanding that 33 Trainpeople agency staff, employed for five years on the Wembley Central group and then sacked, be given staff jobs with London Underground. Photo Andrew Wiard/andrew-wiard.info

The EU’s Agency Workers Directive hasn’t protected us – just encouraged the massive growth of casualisation…

More and more workers find they can only get work through agencies. Over the past few years agencies have evolved from short-term suppliers of casual labour into a systematic tool to undermine wages and union organisation. The EU has made it easier for employers to make that step.

Agency work, or forced self-employment, had long been endemic in a few industries, including construction. Fights against the employment of people on those terms have been sporadic. Occasionally widespread disputes have broken out – such as that in 1972 which resulted in the infamous convictions of the “Shrewsbury 24”.

Spreading

Now these practices have spread to all sectors and many types of work – ranging from warehouse workers to lorry drivers and nurses. Employers now see it as their duty to shareholders to escape from employment law and to evade tax and national insurance payments. Worse, they bully workers into taking part in these schemes, often to impose low wages.

The Agency Workers Regulations came into force on 1 October 2011, implementing the EU Temporary Agency Work Directive of 19 November 2008. It defines a “temporary work agency” as an organisation that supplies workers to work temporarily for hirers.

The EU directive and the UK regulations are supposed to give agency workers the right to equal treatment with regard to basic terms and conditions of employment. So it seems agency workers should be treated no worse than if they had been employed directly. That does not happen.

‘The only way is through workplace organisation.’

The only way to enforce that parity is through workplace organisation and not through the courts. Unions need to organise to ensure that people working in the same roles, alongside one another, are given the same rewards for doing the same work. That means ensuring agency workers are employed on the same basis as directly employed workers. Clearly, this means stopping employers from using employment agencies as a cheap alternative to employing workers on permanent contracts.

The government enacted the regulations to give the lowest level of protection it thought it could get away with. For example there is a qualifying period of 12 continuous weeks before an agency worker has a right to the same “basic working and employment conditions” that apply to comparable direct employees. The regulations also adopt a narrow definition of what counts as pay for the purpose of equal treatment.

The EU directive does not give agency workers a general right to equal treatment in relation to statutory rights, such as protection from unfair dismissal. Agency workers’ rights even where they are enforced are still minimal.

The courts have upheld that view over many years. In a recent decision, Smith v Carillion, Mr Smith was held not to be a worker or employee of the company for which he worked, and so was not protected against acts of anti-union victimisation.

Helping employers

It might look helpful, so social democrats laud the directive as progressive. But it has simply enabled employers to increase their exploitation of workers, leaving tens of thousands of temporary workers out of pocket.

The overall impact of the directive across Europe has been to legitimise and indeed encourage the casualisation of working conditions. It has led to a huge increase in the number of workers employed through agencies and hence without the full rights of directly employed workers.

Under the EU rules, temporary workers are entitled to the same pay and conditions as permanent staff after 12 weeks of continuous employment. As a result, agency workers who have a permanent contract of employment with an agency and are paid between assignments will not have a right to equal pay with directly employed workers.

This is so even where the agency worker has worked for 12 weeks in the same role with the same hirer. Many agency workers sign so-called “pay between assignment” (PBA) contracts without realising that results in lower pay, costing workers around £500 a month in lost wages in some areas.

Loophole

This loophole is known as the “Swedish derogation”. It exempts an employment agency from having to pay the worker the same rate of pay, as long as the agency directly employs the individual and guarantees to pay them for at least four weeks during the times they cannot find them work. Agency workers can then be contracted out to other employers.

More and more recruitment agencies operating in Britain, both large and small, are using this EU-legitimised scam. Thousands of temporary staff working for supermarkets, manufacturers and services firms nationwide have been urged to waive their rights to the new rules, or risk losing their job.

‘The directive has enabled employers to increase their exploitation…it has led to a huge increase in the number of workers employed through agencies and hence without the full rights of directly employed workers.’

As Katja Hall, former CBI chief policy director, said, “Many firms prefer to pay an agency to provide temps using the Swedish derogation rather than face the bureaucracy involved in complying with the directive. This is perfectly understandable and entirely within EU law.”

In many British workplaces agency staff are paid up to £135 a week less than permanent staff, despite working in the same place and doing the same job. Swedish derogation contracts are used regularly in call centres, food production and logistics firms.

The number of agency workers with these contracts has grown by 15 per cent since the recession, with as many as one in six agency workers on them. Industry bodies say that between 17 per cent and 30 per cent of all agency workers are now affected by these contracts.

Tesco used the loophole with its supply chain, allowing agencies to ignore the rules. Tesco said that the Swedish derogation approach had been “recognised” by the British Retail Consortium, the CBI and the government. Other supermarkets and manufacturers followed suit with the PBA model.

The Communication Workers Union has staged a series of protests at call centres, involving temps working for recruitment agency Manpower, who are then supplied to communications giant BT.

Former CWU general secretary Billy Hayes said, “These contracts are legal, but in the same way that the legal tax arrangements of Starbucks, Amazon and many celebrities are morally wrong, we believe these contracts fly in the face of fairness. Both agencies and hirers [employers] are at fault for choosing to use these contracts…”

There are other bad effects for workers. In the health and care sectors, for example, agency work is offered above regular pay rates. But on closer examination this is just another scam. Apparently higher pay rates rely on those staff having to stay out of the NHS Pension Scheme. Employer pension contributions are used to top up the salary scales. But not to the full amount, of course.

Frequently these workers must also enter into “umbrella company” schemes, a dodge to reduce tax paid by the individual. So the state effectively subsidises wages paid by these agencies. And as a bonus the arrangement also reduces the amount of employer national insurance contributions.

In-house

Some local authorities and NHS trusts have set up in-house employment agencies. The directive may make these more common. Last year the government put a cap on the amount that can be spent on agency staff. This has not diminished the pressure for nurses and other health staff to work through umbrella companies and other abusive arrangements. Instead it has institutionalised existing staff shortages.

A survey found that 65 per cent of supply teachers believe they are not paid at the correct level. It also found that 11 per cent of supply teachers working through agencies say they have been asked to waive their legal rights. 68 per cent of supply teachers “said they had not been made aware of the 12 week rule under the directive. Teaching unions need to act to regulate all supply agencies and to insist on national standards for the employment of supply teachers.

The short-term solution of agency work has been turned into a permanent condition for many workers. Many agency workers are employed by an agency for years, all while working for minimum wages, on long, unsocial hours, and with no promotion or training opportunities offered to them. The government keeps no record of the number of agency workers, and has no plan to do so.

Some employers don’t even bother with the pretence of agencies and declare their workers to be self-employed contractors. That means no guaranteed earnings, no pension, no holiday pay and no security. It’s always been around in some areas, but like other abuses, it is growing. And it does not end up much different from zero hours employment. Workers can only fight these dodges by organising in workplaces to challenge them.

All this raises questions about the EU directive. Why was the “Swedish derogation” loophole built into the law in the first place? If its effect is to increase exploitation, and we have seen that it is, what use were its allegedly good intentions?

• Related article: The Shrewsbury 24