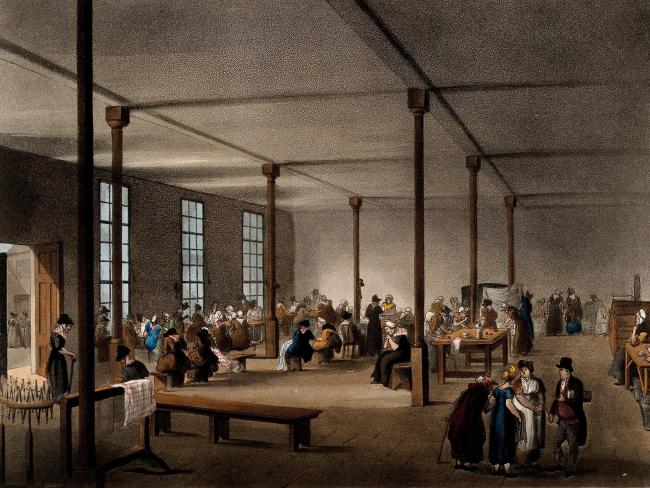

The Workhouse, Poland Street, Soho: the interior. Coloured aquatint by T. Sunderland after A. C. Pugin and T. Rowlandson, 1809. Photo Wellcome Collection (Public domain).

Capitalists have never wanted to pay workers who through illness – or because there is no work for them – are unable to work. The priority, though, is not better benefits. It is work for all who can…

Society needs workers. Work by hand and brain produces what is needed for existence, which includes the safety net of welfare payments for when workers are sick or otherwise not able to work.

Capitalism relies on un- and under-employment (Marx’s “reserve army of labour”) to ensure workers are kept on their toes, in competition with each other for jobs and pay.

Currently capitalists hope that AI will replace many jobs, just as power looms replaced hand loom weavers, and many similar changes. Employers keep the drudgery of manual or clerical labour, especially while there are plenty of workers available – until the point when they introduce new machines, or these days IT.

Discarded

Then those workers and their accumulated skills are discarded and replaced with workers who they hope will be cheaper or less skilled. But it does not work like that. Power looms also take skill to build and operate, just different from handlooms, and one worker with a machine can produce far more than what went before.

What’s happening now with AI is little different. While it can be used to create new drugs and engineering designs that would have been impossible or very difficult a short time ago, it also replaces call centres and similar processes with automation that aims to keep consumers, customers and other businesses at bay.

Work becomes fragmented and even more alienating – with home working, outsourcing, contractors, dispersed production and delivery all enabled by technology which should be a great benefit to workers and society. But workers do not control it – and until they do, changes to production will enslave rather than liberate.

And employers don’t want to have to pay workers who, for whatever reason, aren’t working.

What of those not in work – whether temporary or permanent, voluntary or not? Workers fought for, and now expect, to be paid more than is just necessary to live each week and not to be left destitute when not working. The higher wages and secure jobs they achieved are the antithesis of the gig economy (which is not “modern” at all, but echoes the worst aspects of casual work in the past).

Along with these achievements, built on workplace struggle, other benefits were won – like the old age pension in 1909 (paid at 70 then, reduced later and now heading back that way). Unemployment and sickness benefit started with workers’ mutual organisations (because they earned enough to put some away). Only later did the state take responsibility.

Undermined

The capitalist class especially doesn’t like it that retired people are living longer so it wants an increased state pension age and makes perpetual demands to reduce the cost of pensions. And despite the rhetoric that “we” must save for retirement, governments and employers have been undermining the value of occupational pensions for decades.

Welfare “benefits” now come in a wide range – unemployment, income support, sickness, disability support, housing support, retirement pensions, and a whole lot more. The simple idea of a regular contribution entitling payments is long gone.

This progress was not given by benevolent employers, but wrung out of them over decades. Yet the strategy of ensuring that workers can live in dignity when sick or retired isn’t a substitute for the struggle for jobs and skill – or the fight for wages.

‘Demands for “fairness” in the face of arbitrary cuts to benefits cannot be substituted for the fight for wages and jobs…’

The ruling class and their governments have always sought to undermine and restrict benefits, almost as soon as they are won. That reaction is unchanged from the eighteenth century, when they would not pay the poor rate (“workers are lazy and that’s why they are poor, they don’t deserve support”).

This developed into the hated workhouses, which lasted until the third decade of the twentieth century – fresh in the memories of workers as the welfare state evolved after World War Two.

Workers who aren’t gainfully employed are now said to be the problem, a drag on growth and productivity. The list is wide: older workers who won’t go back to work; feckless youth who are always sick; disabled workers who want unreasonable adjustments.

Employers try to evade responsibility – blaming workers for the shortcomings of capitalism, which only seeks to exploit for profit. Opportunity and potential contribution to the wealth of the country are not considerations – and ultimately jobs are moved out of Britain.

All attempts to cut benefits and the cost of welfare by tightening conditions and reducing funding end up in confusion and disaster, such as that caused by the current Labour government. But this is just a continuation of the universal credit shambles of its Coalition and Conservative predecessors.

Yet workers and their unions can become sidetracked with demands for better benefits as an end in themselves. Demands for “fairness” in the face of arbitrary cuts to benefits cannot be substituted for the fight for wages and jobs. Neither should unions seek to keep those able to work on benefits – rebuilding requires the energy and commitment of all.

Of course it is right to criticise and fight capricious decisions like the cut to winter fuel allowance. But these are only defensive actions when set against the real underlying issues – in that instance rising energy costs and benefits not keeping up with inflation.

Workers must demand work and wages, to acquire skills and to be able to use them. Adequate benefits and welfare can’t be set aside from or prioritised over that.