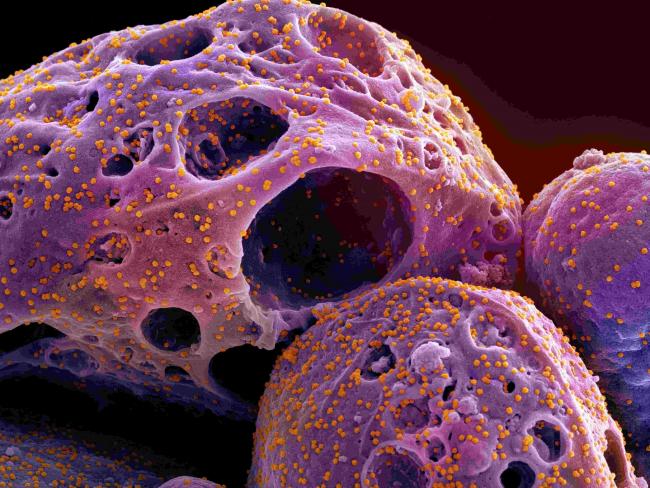

The bug that brought Britain to a virtual standstill: novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (Omicron). Image NIAID/NIH via Flickr, Public Domain.

Are we learning anything new from the UK Covid Inquiry? The answer really matters, given the inquiry is costing the country a lot of money…

Since its launch in June 2022, the Covid Inquiry has cost £192 million to date and is estimated to cost over £230 million by its conclusion. The BBC reported that, in addition to these direct costs, the government has spent over £100 million in preparing its submissions.

The inquiry is split into ten modules. Hearings are expected to conclude in March and the final report is due by summer 2027. In addition to the costs of the Inquiry itself, Whitehall departments, devolved administrations, and others have spent millions in legal fees defending themselves at our expense.

Since the Inquiries Act 2005 came into effect, twenty-four statutory inquiries have been completed. The Covid Inquiry is by far the most expensive conducted under this framework. The overall bill is now close to the costs of building one of the smaller district general hospitals on the government’s list of those needing most urgent replacement.

Reservations

Unsurprisingly, workers were already expressing their reservations about the inquiry’s usefulness. The report for Module 2 (decision making and governance), published on 20 November, further increased those concerns.

The headline was that the UK government and all the devolved administrations had done “too little, too late” during the pandemic. This was not news. So the inquiry team added a specific figure alleging that if the UK government had locked down a week earlier, 23,000 lives would have been saved in England.

This was the cue for the media to resurrect stories about what Johnson and Cummings did or didn’t do in 2020. These were not new either, but made for colourful headlines. The details in the report show a different picture.

The 23,000 figure was an estimate based on one piece of modelling, for England only. Even the report’s executive summary says it would be wrong to conclude that bringing in lockdown a week earlier on 16 March would necessarily have reduced the overall death toll. Many other factors could have reduced or increased the number of deaths as the pandemic progressed.

Less prominence was given in the media to the governance theme of module 2. It found that there were no clear structures to facilitate the UK government’s working with the devolved administrations during an emergency.

The administrations in Cardiff, Edinburgh and Belfast were all criticised for “relying too heavily on the UK government” when the pandemic began – as well as trying to be different. And the UK government was condemned for failing to communicate efficiently as the months progressed.

This gives the lie to claims from the separatists that they handled the pandemic perfectly, unlike Westminster. Not surprisingly there was a recommendation, “To establish structures to improve communication between the four nations during an emergency”. Not to “improve structures”, but to “establish structures”! How long did it take to come up with that nugget?

Inability

The government does not have to adopt the inquiry’s recommendations, but it must respond to them. We did learn that while Keir Starmer struts the world stage as the self-appointed leader of the Coalition of the Willing to further war in Europe, he leads a government lacking the ability to coordinate during a national emergency.

Those in areas of Wales and Scotland bordering England experienced different lockdown rules in 2020. Workers saw back then that there were coordination problems. The real question is, why are structures for improved coordination not in place five years down the line? Instead we have a weak recommendation awaiting a response from a weak government.

Will anything improve? Labour’s manifesto promise was for more devolution rather than increased national cohesion. This recommendation for better coordination does not sit well with their chosen policy direction.

Other key recommendations include:

• Improving consideration of the impact that decisions might have on people – both on the illness and by the steps taken to respond to it.

• Creating expert groups to advise on the economic and social implications of policy decisions, not just on the medical science.

• Ensuring decisions – and their implications – are clearly communicated to the public.

• Enabling greater parliamentary scrutiny of emergency powers.

These do not look like “new knowledge”. Surely all have been discussed in workplaces, schools, care homes, hospitals, and on street corners since 2020? And with no mechanism for enforcing action on these recommendations, there is no guarantee of change or improvement.

Craven

This juggernaut of an inquiry will roll on, and to stop it will be difficult. It feels as if someone should at least say that the emperor has no clothes. But don’t rely on the politicians or Westminster, Edinburgh or Cardiff, to do so. Their craven hope is to embarrass their political opponents and avoid criticism themselves.

‘Someone should at least say that the emperor has no clothes…’

There will probably be another pandemic: when and how severe, we cannot predict. We have already learnt the lessons of Covid-19: the successes of rapid vaccine development and deployment (despite government); the negative lessons of over-zealous lockdowns (Starmer wanted more); the bad effects of closed schools and enforced working from home.

We learnt too that the only measures that work in such a crisis are those that the working class itself devises and implements. Many workers took the initiative without being told, something Johnson and Starmer can’t understand. The public must assert itself over public health. We trust capitalist governments for protection at our peril.