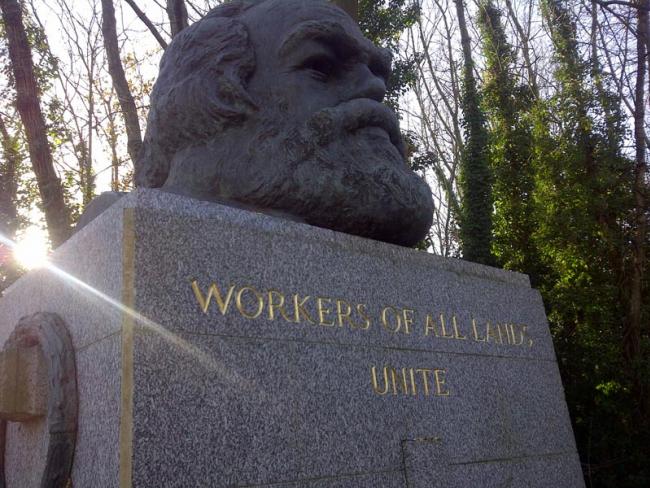

Karl Marx’s grave, Highgate Cemetery, London. Photo Workers.

Nearly two centuries ago Karl Marx found the practical basis and connection that exists between thinking and being and action…

Karl Marx performed many different tasks in a busy life, one dedicated exclusively to advancing the cause of the working classes across the world. During his lifetime he became an economist, a historian, a journalist, a leader of working class struggle, an advocate for revolution, and a philosopher.

His various activities, always interacting, informed each other. Most people are familiar with his other involvements, but possibly fewer are aware of his remarkable contribution to philosophy and how this shaped his political activity.

Why was philosophy so important to Marx? And how did grappling with philosophical thinking help develop the whole of his trailblazing outlook?

As a young man Marx first studied law, then history, before pursuing a doctorate on ancient Greek philosophies of nature. From the start, he wasn’t just immersed in the ideas of the distant past, he engaged directly with German philosophical contemporaries, such as Georg Hegel and Ludwig Feuerbach.

In his early writings, Marx pursued an interest in alienation – people distanced from their work and their wider world. Though he did not return to the subject much in his later works, his thoughts still have significance, particularly when he addresses the question of alienation at work.

Marx identified different dimensions of alienated labour in contemporary capitalist society. One such was that immediate producers are separated from the product of their labour because they neither own nor fully control the product they make.

‘For Marx, reality is best understood as an ongoing historical process…’

Another is that these producers are separated from other individuals, countered to a certain extent by workers’ collective organisation. So when workers insist on a common professional stance to their work, do they actively resist and repel alienation?

A wide-ranging thinker, Marx fashioned a synthesis of history, economics and philosophy.

He studied in-depth the philosophical categories of materialism, which holds that matter is the primary constituent of reality, and dialectics, which seeks to understand change through examining and resolving contradictions.

Marx took what was positive from both these strands of thinking whilst simultaneously identifying weaknesses in previous interpretations. He proposed new directions for both.

From Feuerbach he developed the view that reality is not something spiritual but something material. Marx called this thinking materialism. To Marx, the ideal is nothing else than the material world reflected by the human mind, and translated into forms of thought.

From Hegel he inherited the idea of human destiny, of the self-creation of man as a process, of history having a movement, of nothing staying the same, of the idea of right being held by the society as a whole, of the dialectic being the motor of a system in motion.

But he rejected Hegel’s “Absolute Idealism” and his view that spirit is the very essence of existence, as well as his worship of the Prussian state. Marx transformed these notions into new interpretations and in a different direction.

For Marx, reality is best understood as an on-going historical process: the key to understanding reality is to understand the nature of historical change. He noticed that development proceeds in spirals rather than straight lines. Inner impulses cause development by leaps, catastrophes or revolution; that development is imparted by contradictions acting within a given society.

From his studies, Marx concluded, “The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways: the point however is to change it.” This famous epigram was one of eleven theses rebutting the ideas of Feuerbach. Though never published in his lifetime, it is inscribed on his tomb in Highgate Cemetery.

His philosophical conclusions weren’t self-contained but shaped his study of economics and history. Capital analyses the material basis of capitalism starting with a commodity. His prompt pamphlet praising the revolutionary Paris Commune in 1871 owes much to his knowledge of dialectics and materialism.

Unyielding

Marx had an unyielding belief in the endless possibilities of a working class. Where did it come from? Most probably it came from his practical experience of working with French, German and British workers, as well as from his work of creating the First International.

Yet perhaps this belief was also generated and sustained from his philosophical conclusions. For a working class is the only material force able to effect revolutionary transformation; it is the only part of the contradiction able to resolve the question of power.

In Marx’s day, dialectics and materialism were separate. When working class revolutions took place in the twentieth century, these two concepts were grandly combined into dialectical materialism, but this created a new problem.

The new socialist societies gave this outlook a formal academic cachet it didn’t require, by creating institutes and universities of Marxism-Leninism and putting it as a subject on school curricula. In the process what should have been a practical philosophical tool was unintentionally sidelined into a learn-by-rote mantra, an unpractical catechism.

This quasi-religious approach not only bored people silly but also deadened the applied, creative imperative behind dialectics and materialism. Their only useful purpose is to indicate or produce the best applications, methods and pathways to solve the problems and crises facing workers under capitalism.

Everyone who wants progress for workers should keep Marx’s philosophy active, not consign it to a quaint historical archive away from the urgencies of life. What is needed is simple: a spirit of thinking, a philosophical approach, a compass to navigate a way out of capitalism’s absolute decline.